Me-On-Medicine

Mar 22, 2022

I’ll never forget the experience of awakening when medicated on an antipsychotic for the first time. It left such an impression on me that I wrote about it a few years later. So here is what I wrote, those many years ago, about what it was like for me to wake up for the first time on an antipsychotic drug:

For three days I have laid pasted to this hospital bed in a drugged and dreamless sleep. I am some christ, broken and laid into a therapeutic exhaustion where dreams do not speak of resurrection. Small rivers of spittle leak and string onto my chest and my arms are too drugged and stiff to reach up and wipe off the shame of it. A tear of what is left of me, crawls down my face and genuflects into the humiliation of it all. Once my body could move with grace and youth but now some old woman has crawled into these bones and they are nothing more than arthritic crutches, propping me up on some bed that is not mine.

The point I want to make is that I was completely alone in this experience. Staff kept telling me the meds would help me return to normal. My parents were visibly relieved that I was on medicine. My treatment team said I would need to take these meds for the rest of my life. Everyone kept telling me how important it was for me to be compliant with medication. But no one asked me about me, or should I say, me- on-medicine. Nobody offered to accompany me on my journey into me-on-medicine.

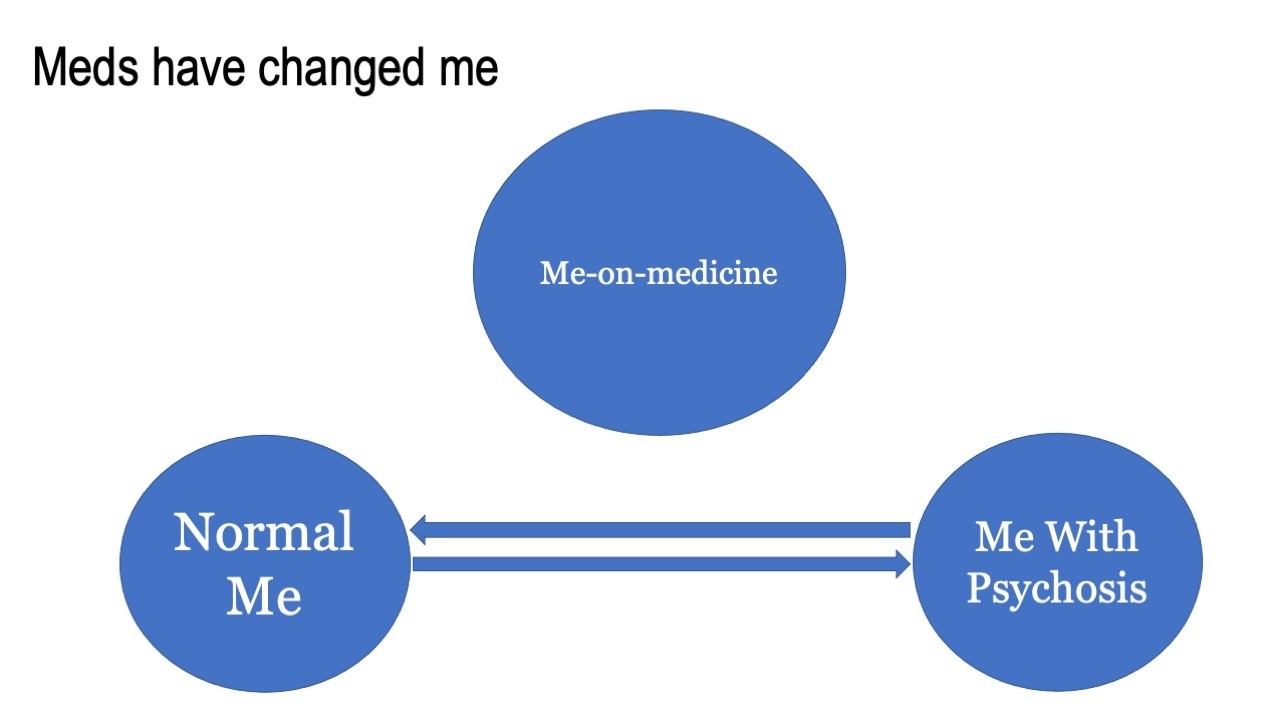

You see, it is widely assumed that psych meds, in time, return us to normal. In other words, there is the me I know before psychosis: The athlete with lots of energy, little love of schoolwork, and all the rest. That was regular me, normal me, or just Pat. Then came these strange and frightening experiences that got diagnosed as psychosis. When I was administered antipsychotics, people assumed I would eventually return to “normal me”. But I did not simply return to “normal me”. Instead, a third state emerged. I call this third state Me-On-Medicine.

Me-on-Medicine was a me I did not recognize. I did not recognize myself that day, or in the weeks or months to come. My family and team were pleased I was taking medicine. But there was no one to support ME on my journey into Me on Medicine.

Most fundamentally, I experienced that meds had changed me. Some of the changes, like being able to sleep, were welcome. But many of the changes were not:

There were changes to my embodied self – the dry mouth, the bad breadth, the slowness, that little ball of dried saliva at the corner of my mouth, the weight gain.

There were also changes to my emotional and spiritual self – the flatness, the muted emotions, like I was in a kind of chemical hibernation.

There were also changes to my beliefs about who I am now that I am a person taking meds – If I take meds does that mean I’m crazy?

And finally, there were all the questions – really hard questions – that came up:

Do I accept the Me-I-am when I’m on meds? Do I reject that me? Do I accept the diminished capacity to feel in exchange for the ability to fall asleep at night? Am I willing to lose my edge in athletics in order to be able to focus on my schoolwork rather than my troubling beliefs?

These questions, these existential negotiations if you will, are as complex and as nuanced as the individuals we are working with.

My recent work is called Medication Empowerment. It's an intervention that peer supporters, clinicians and families can use to support folks in having a voice and choice in their treatment. I wish Medication Empowerment was available when I was first diagnosed with schizophrenia.