When Help is Not Helpful

Sep 06, 2005

Sometimes help is not helpful.

Early in my recovery, after a brief interview with a psychiatrist, I was taken to a room and injected with an antipsychotic drug called haloperidol. When I awoke from that drug-induced stupor, I could barely recognize myself. My tongue was thick. My vision was blurred. Saliva drooled and leaked down my face. The medication made it hard to swallow, so food spilled and soiled my shirt. I began to smell of last night's supper. Just weeks before I had been a strong athlete who excelled in sports. Now I was in a chemical straightjacket. I moved stiffly and slowly as if some old woman had crawled into my body and my bones were nothing but arthritic crutches, propping me up against the wall of a mental institution.

Drugged on haloperidol I could not feel anything. I did not care about anything. I could not smile or laugh or cry or think. In the distance, I could still hear the auditory hallucinations, but they had lost their power to grab my innards and shake me to attention. They drummed like a dull ache in the background and were easy to ignore. Everything and everyone else was easy to ignore because I cared about nothing and felt nothing. I had been muted. I had become the muted body. I had been silenced - erased and disappeared under the tyranny of those small green pills.

It is widely assumed that antipsychotic drugs are helpful because they suppress psychosis and restore one to a more familiar sense of self. In my experience, antipsychotic drugs at these high dosage levels were not helpful. Haloperidol did not return me to a non-psychotic, more familiar self. Rather, it delivered me into a negation of myself, an absence, a silenced echo of my former self.

Haloperidol replaced me with the drugged-me. And worst of all, the professionals kept telling me how good this medication was for me. They kept telling me I would have to take this medicine for the rest of my life. They said I should be grateful modern psychiatry had a medicine that could so quickly restore my functioning. The psychiatrist said my hallucinations and delusions were gone. The symptoms were abating he said. I was more in control and I was stabilizing he said. From my perspective, however, things appeared quite different. I did not feel better. The so-called hallucinations were still there although they were no longer a bother to the people around me. I was not more in control but rather, I felt controlled by the medication. I was not stabilizing. Rather I was becoming a shadow of my former self, unable to think or feel. I was not beginning to function. Instead, I was learning to play the game in order to get discharged from that institution as soon as possible. I was not grateful for this medicine. I was not grateful for this help. As far as I was concerned, this help was not helpful.

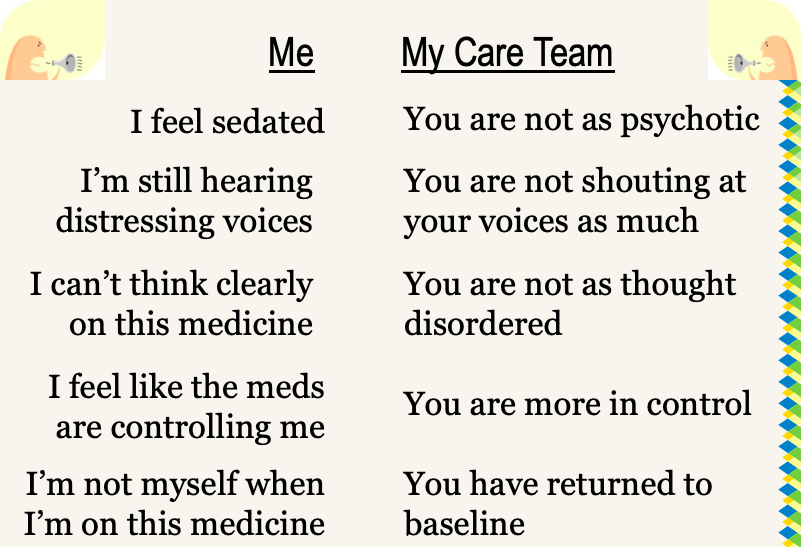

What I am describing here is a clash of perception between the psychiatrist and myself. This chart summarizes some of the main points of that clash of perception:

It is important to remember that this clash of perceptions I am describing went largely unspoken and unacknowledged. The psychiatrist and I did not sit down and have a thorough discussion of our divergent perspectives. It is also important to see there is a terrible power imbalance here. This clash of perception occurred between a psychiatrist and me during one of my most vulnerable times. Because of his enormous power in relation to me, the psychiatrist's interpretation of me became the only valid story. His story about me became the truth and my story, my experience, and my voice were silenced. What I am describing, therefore, is a double silencing. The first silencing was imposed by a therapy (haloperidol) that muted me. The second silencing was imposed when my experience of the therapy was ignored and the professional's interpretation of the outcome of therapy was prescribed as the only truth.

The silencing I am describing is not confined to people with psychiatric disabilities. Silencing people with disabilities through the assertion of the expert's professional opinion occurs routinely. It is not uncommon for an expert to declare that a person is making good progress in a sheltered workshop while the person with the disability feels like a failure because they are not working a real job. It is not uncommon for a rehabilitation specialist to applaud the progress a child is making in speech therapy, although the child is quite clear they are tired of all the therapy and would rather play with kids in the neighborhood after school. In these and thousands of other instances, the professional's interpretation becomes the official story while the stories, the voices and the experiences of disabled people are silenced.

Who gets to say if a therapy is working? Whose directives are followed and whose are silenced? Who gets to say if professional help is helpful? I would propose that help which ignores the perspective and autonomy of the person with a disability is toxic help. Toxic help is, at best, a waste of time, money and resources and, at worst, toxic help hurts and may even kill.

Help, and in particular toxic help, is not a topic that is discussed often in professional rehabilitation cultures. The nature of help is one of those topics about which we are often silent because we are too busy being helpful to stop to talk about it. But we must break that taboo. We must dare to talk about help because power, including the power to oppress, often disguises itself as help. Power-disguised-as-help is used to silence disabled people. Paolo Freire (1989) says that oppressive power submerges the consciousness of the oppressed into a culture of silence. Toxic help oppresses and silences people with disabilities.

Help isn't help if it's not helpful. Help that is not helpful can actually do harm. Being helpful requires that professionals ask us what we need. But asking is never enough. Professionals must also listen to what we say. In this way, help becomes something that is co-created between the disabled person and the professional. When help is co-created as an explicit agreement between the professional and the individual, then silencing is avoided.

In my opinion, one of the best methods for amplifying the voice and values of those of us who are disabled is the shared decision-making process. In this process, the clinician and service user come to an agreement on:

- what the service need is,

- what the course of rehabilitation will be,

- what the desired outcomes of services are and

- what the respective responsibilities of each party will be in achieving those outcomes.

It seems to me that the shared decision process is more than a method. It is an ethical obligation that makes explicit the power of the professional and brings it into alignment with the voice and directives of the disabled person.